#indieweb

Storing posts by juggling with Git internals

I have been wanting to rework the core of this website for a couple of years now, but since the current setup still works, and since I have many other things to do, and finally since I am very picky about how I want it to work, I have never really finished this part at all. This makes me stuck at the save version of this site, both visually as behind the scenes.

Now that I am in between jobs I wanted to work on it a bit more, but I still do not have time enough to fully finish it. I guess it all comes down to a few choices I have to make regarding trade-offs. In order to make better decisions, I wanted document my current storage and the one I have been working on. After I wrote it all out I think I am deciding not to use it, but it was a nice exploration so I will share it anyway.

The description heavily leans on some knowledge about Git, which is software for versioning your code, or in this case, plain text files. I will try to explain a bit along the way but it is useful to have some familiarity with it already.

tl;dr: I did fancy with Git but might not pursue.

How it is currently done

At the time of writing, my posts are stored in a plain text format with a lot of folders. It is derived from the format which the Kirby CMS expects: folders for pages with text files within it, of which the name of the text file dictates the template that is being used to render the page. In my case, it is always entry.txt.

I have one folder per year, one folder per day of the year and one folder per post of the day. In that last folder is the entry.txt and some other files related to the post, like pictures, but also metadata like received and sent Webmentions.

An example of the tree view is below. It shows two entries on two days in one year. Note that days and years also have their own .txt file that is actually almost empty and pretty much useless in this setup, but still required for Kirby to work properly. The first day of the year my site is broken because it does not automatically create the required year.txt (or did I fix that finally?).

./content

└── 2022

├── 001

│ ├── 1

│ │ └── entry.txt

│ │ ├── .webmentions

│ │ │ ├── 1641117941-f6bc3209f3f33f0cb8e4d92e5d46b5090b53aa11.json

│ │ │ └── pings.json

│ └── day.txt

├── 002

│ ├── 1

│ │ ├── some_image.jpg

│ │ └── entry.txt

│ └── day.txt

└── year.txtAlso note that there is a hidden .webmentions folder which contains a pings.json for all the sent webmentions and a JSON file with timestamp and content hash in the name for every received webmention. Not in the diagram but also present are some other folders for pages like ./login/login.txt (because that is how Kirby works) and ./isbn/9780349411903/book.txt (for books).

All these files are stored in a Git repository, which I manually update every so often (more bimonthly than weekly, sadly) via SSH to my server. I give it a very generic commit name (’sync’ or so) and push to a private repo on Github, which takes a while because the commits and the repo contain all those images and all those folders.

What is wrong with this

The main point of wanting to move off of this structure by Kirby, is that it requires those placeholder pages in my content folder. I have no need for a ./login/login.txt: the login page is just a feature of the software and should be handled by that part of the code. But at least that file contains some text for that page: the files for year.txt and day.txt are completely useless.

Another point is that I want to make the Git commits automatically with every Micropub request: Git provides me with a history, but only if I actually commit the files once I changed them. Also, if I do not push the changes to Github, I have no backup of recent posts.

The metadata of the received and sent Webmentions are now also available in the repo. This is nice, as it stores the information right next to the post it belongs to, but on the other hand it feels kind of polluting: these Webmentions contain content by others, where as the rest of the content is by me. There is some other external content hidden in the entry.txt file but I’ll get to that later.

The last point is that the full size images are stored in the repo and every book and article about Git says that you should not use it to store big files in it. Doing a git status takes a while and also the pushes are much slower than any other Git repository I work with.

Git history: the Git Object Model

Before I go further into the avenue I am taking to solve the problem, I need to explain a bit about the Git Object Model, also known as ‘how Git works under the hood’. For a more thorough explanation, see this chapter in the Git Book.

As you’ll learn from that chapter, every object is represented as a file, referenced by the SHA1 hash of its contents. And there are three (no, four) types of objects:

- blobs, which are the contents of files tracked by Git (and thus also the versions of those files)

- trees, which are listings of filenames with references to blobs or other trees. These trees together create the file structure of a version.

- commits, which are versions. A commit contains a reference to the root tree of the files you are tracking, a parent commit (the previous version) and a message and some metadata.

- tags, are not mentioned by the chapter, but do exists: these look like commits, but create a way to store a message with a tag (making annotated tags, I’ll explain plain tags soon).

Note that Git does not store diffs, it always stores the full contents of every version of the file, albeit zlib compressed and sometimes even packed in a single file, but let’s not get into that right now.

Git’s tags and branches are just files and folders (they can have / in their names) which contain the hashes (names) of the specific commits they point to. The tags can also point to a tag object, which will then contain a message about the tag (which makes them ‘annotated tags’).

This all brings me to the final point about my storage: for every new post, Git has to create a lot of files. First, it needs to add a blob for the entry.txt, possibly also a blob for the image and blobs for other metadata. Then it needs to create a tree for the entry folder, listing entry.txt and if present the filenames of the images and metadata files. Then it creates a new tree for the day, with all the existing entries plus the newly created one. Then it creates a new tree for the year, to point to this new version (tree) of the day. Then it creates a new tree for the root, with this new version of the year in it. And finally it also needs to create a commit object to point to that new root tree. Every update requires all these new trees. The trees are cheap, but it feels wasteful.

Also note that a version of a file always relies on the version of all other files. This is what you want for code (code is designed to work with other code), but it does not feel like the right model for posts (I might come back on this tho).

And there is also the question of identifiers: currently, my posts are identified as year, day of year, number (2022/242/1), but especially that number can only be found in the name of the folder and thus in the tree, not in the blob. I have not yet found a good solution for this, but maybe I am seeing too many problems.

The new setup

To get rid of some of the trees, I tried to apply my knowledge of the Git Object Model to store my posts in another way. To do this, I used the commands suggested by the chapter in the Git Book in a script that looped over all my files, to store them in a new blank repo to try things out.

For each year, for each day, for each post, I would find the entry.txt and put the contents in a Git blob with git hash-object -w ./content/2022/242/1/entry.txt. The resulting hash I used in the command git update-index --add --cacheinfo 100644 $hash entry.txt to stage the file for a new tree. I would do that too for all images and related files, and then I would run git write-tree to write the tree and get the hash for it and git commit-tree $hash -m "commit" to create a commit based on it (with a bad message indeed). With that last hash I would run git update-ref refs/heads/2022/242/1 $hash to create a branch for that commit. (I contemplate adding an annotated tag in between, for storing some metadata like ‘published at’ date.)

This would result in a Git repository with over 10,000 branches (I have many posts) neatly organised in folders per year and day. When one were to check out one of these branches, just the files of that posts will appear in the root of your repo: there are no folders. When you check out another branch, other files will appear. This is not how Git usually works, but it decouples all posts from one-another.

Multiple types of pages

The posts I describe above all follow the year-day-number pattern because they are posts: they are sequential entries tied to a date. There are other objects I track, though, that are not date-specific. One example is topical wiki-style pages: these pages may receive edits over time, but their topic is not tied to a date. (I don’t have these yet.)

Another example is the books that I track to base my ‘read’ posts off. I haven’t posted them in a while, but I would like to expand this book collection to also include other types of objects to reference, such as movies, games or locations. These objects also have no date to them attached, at least not a date meaningful to my posts.

I could generate UUIDs for these objects and pages, and store branches for those commits in the same way Git does store it’s objects internally, with a folder per first two characters of the hash (or UUID) and a filename of the rest:

./refs/heads

├── 0a

│ ├── 8342d2-d6f1-4363-a287-a32948d04eaa

│ └── edcb13-433c-48d2-b683-a407c3a88f57

└── 3d

├── 243a27-114e-4eee-9bd8-2a51b01939e6

├── 25965b-2da5-422d-abce-f3337fa97fc4

└── 611b59-499a-48a0-b931-afe06192e778I could even reference the same post/object with multiple identifiers this way. Maybe I want to give every book a UUID, but also reference it by its ISBN. The downside to that, however, is that I need to update both branches to point to the same commit once I make an update do the book-page.

Drawbacks of the approach

The multiple identifiers are probably not feasible, but there are some other drawbacks too. My main concern is that it is much harder to know whether or not you pushed all the changes: one would have to loop over all 10,000+ branches and perform a push or check. In this loop you would probably have to check out the branch as well. It is of course better to just push right after you make a change, but my point is that the ‘just for sure’ push is a lot of work.

Another drawback is actually the counter to what I initially was seeking: wiki-style pages might actually reference each other, and thus their version may depend on a version of another page. In this case, you would want the history to capture all the pages, just as the normal Git workings do. My problem was with the date-specific posts, but once you are mixing date-specific and wiki-style pages, you might be better off with the all-file history.

One problem this whole setup still does not solve is that of large files. The git status command is much faster for it does not have to check all the blobs in the repo to get an answer, but the files are still in the repo, taking up space. And there do exist other solutions for big files in git, such as Git LFS, the Large File Storage extension.

Also, I am still not 100% sure it is a good idea to store metadata in the Git commits and tags. When we already store the identifier in the tree objects, I thought I could also add the ‘published at’ date into the commit. Information about the author is already present, and as my site supports private posts, it also seemed like a reasonable location to store lists of people who can view the post. But again, maybe that should be stored in another way, and not be so deeply integrated with Git.

Conclusion

It was very helpful to write this all out, for by doing so I made up my mind: this is just all a bit too complicated and way too much deeply coupled to Git internals. I would be throwing out the ‘just plain text files’ principle, because I would store a lot of data in Git’s objects, which are actually not plain text, since they are compressed with a certain algorithm.

My favourite Git GUI Fork is able to work with the monstrous repository my script produced, but many of the features are now strange and unusable, because the repo is so strangely set up. I would have to create my own software to maintain the integrity of the repo and that could lead to bugs and thus faulty data and maybe even data loss.

I still think there are some nice properties to the system I describe above, but I won’t be using it. But I learned a few new things about Git internals along the way, and I hope you did too.

When @hacdias.com posted about our conversation about post topics I couldn’t stay behind to also formulate my part of it in a blogpost.

Currently I have various feeds for various post types. I don’t want to link them all here, in case I want to change them around, but I have different feeds that only show my likes, my photos, my replies, etc (you can probably guess the URLs).

These feeds are relatively easy to set up: does it have a photo? Then it’s a photo. Does it have a title? Then it’s an article. This post doesn’t have any, so it’s a note. I have a few of those rules set up and they fill these pages.

But when you scroll through my photo feed, you will also see drawings. When you scroll through my notes, there are various topics represented. It is not that bad right now, but that is mainly because I don’t post as much as I could, because I don’t want to bore my readers with topics they don’t want to follow.

On social media, we live a siloed life, and the people on the IndieWeb are trying to bring that all back to their own site. But, in the siloed life, we can pick the silo for the post. ‘Insta is for friends, Twitter is more business, Reddit is shitposting’, something like that. Sometimes the silo is aimed at a certain kind of post, sometimes it is just the kind of bubble you created for yourself on that silo that makes you post a certain way.

On the IndieWeb, I have only one site. Of course I can get multiple – I have – but I like having all my posts in one place. But I also want to give people options for how to follow me, different persona to share posts with.

I do have tags but most are not that useful. Most of them only contain one post, and also, most of them are very specific. I like the indieweb and vim tags, for they are quite topical, but those are exceptions.

At one point (not now) I would like to divide posts up into probably five rough categories. The homepage might still show a selection of all, and there will also be a place to actually see everything, but I think these categories make sense to me:

- professional / helpful for all those posts in which I share something about IndieWeb, Vim, something about programming, something I learned

- personal for stories about what happened in my life, maybe also some tweets, the more human connection

- too personal for checkins, books I’ve read, food I’ve eaten, movies I’ve watched, still about life but without commentary

- art for those good pictures, occasional drawings, fiction stories, the things I post too little

I said five and I posted four, because I don’t think this is final. I might also want to add a ‘current obsession’ category, to blog about those things I am deeply into. (There has been posts about keyboards here, you missed Getting Things Done, currently I am into the game of Go again.)

A last category I might also need is ‘thinking out loud’, as this is a post that would fall into that. For what is worth, I’ll post it anyway.

Ik doe dit dus al jaren: ook al tweet ik niet veel, elke tweet staat ook op mijn eigen site. Het archief downloaden is de eerste stap, maar een eigen domein de belangrijkste. Kan eng klinken maar ook jij kan er gewoon een registreren.

Showing incorrect IndieAuth redirect_uri to the user

Last Thursday I started using my new IndieAuth endpoint, which I can use authorize apps build by others (like the Quill Micropub client), to do stuff with my site (like posting this blogpost for example). In the following weekend I added a lot more validations than just my password, making it a safer endpoint.

One of these validations is the redirect_uri. My previous endpoint already showed this to me on the login-page, so I could manually inspect it, which is a good practice. The spec, however, describes that one should fetch the client_id (which is a URL) and look for a link with the rel-value of `rel="redirect_uri", which can be either in the HTML or in the HTTP Header.

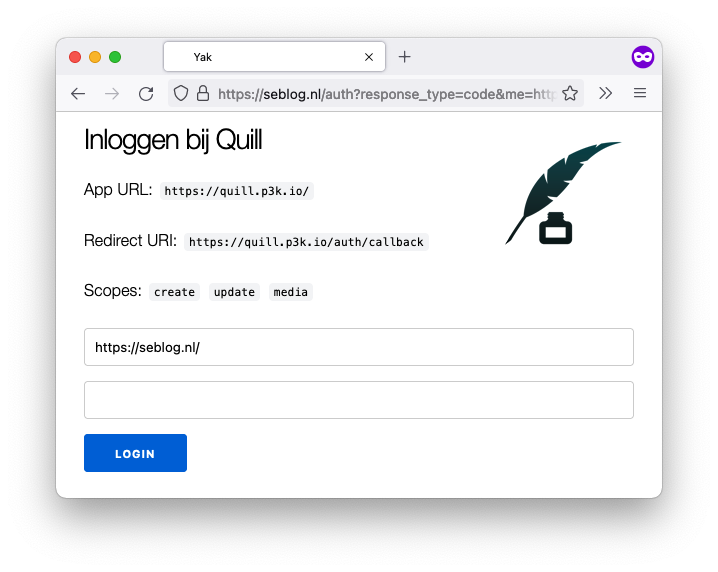

So this is what it (currently) normally looks like:

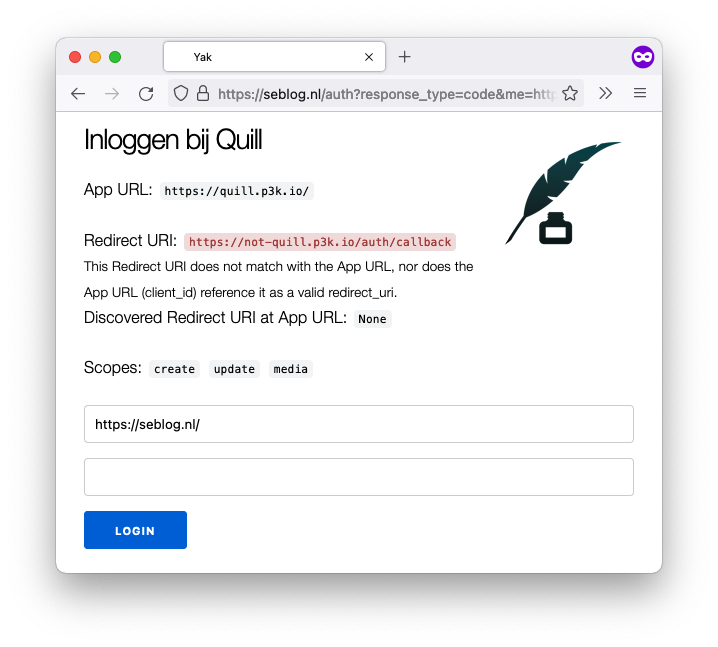

And this is what it looks like when the redirect_uri differs from scheme, domain and/or port, and is also not present in at the client_id.

Note that it is okay for Quill not to advertise another redirect_uri, for it is redirecting to a URL with the same scheme, domain and port. It only needs to add the link if it wants a URL where one of these are different. It is now clearer that someone who is not Quill is trying to steal a token.

I think I made it in time for IndieWebCamp Düsseldorf to fix my IndieAuth? If you are reading this, Quill worked, and I can get some sleep before the trip tomorrow.

Homebrew Website Club London

So, I am not in London and I am not even in the precise timezone as London, but since The Situation is still keeping us home, I got to attend Homebrew Website Club London.

It was mostly just some chatting about smoke detectors, automated blinds and visits to city water reservoirs, as one does on a HWC. We had a few on-topic points as well.

I told about the upcoming birthday of Seblog.nl, tomorrow, which got us down the path of looking up old versions of websites. Much is saved, but many things are lost as well. One thing we came to: if you are starting to code your own website, please learn how to use version control as soon as possible. I (and others) have lost old versions of our sites because we kept overwriting the old files with new changes. If I had discovered Git (or any other version control) earlier, I would have had the oldest versions still.

As a note to myself: I should read Peter's article that he mentioned, which is about this 'content archeology': bringing back old home-pages. I doubt I have enough time to excavate my own first version of Seblog.nl before tomorrow.

Calum also showed his new bookshelf page. It reminded me of my own page called /bieb (short Dutch for 'library'), and now I want to revisit that page as well. The past month, I've been playing around with Obsidian and this would be one of those places where my site could integrate with it. (Both Obsidian and the current iteration of my site run on raw text files.)

I also shared some of my plans around this integration but I am not ready to share those here. (Most of my projects become vaporware, sadly.) However, I feel encouraged that my idea was not totally a bad idea. (Only slightly.) That's why I like going to HWC's: they spark ideas and / or bring them further.

Het ziet er naar uit dat Frank problemen heeft met IndieNews, dus ik probeerde eens wat, zag de foutmelding en dacht: hé, dat kan ik wel oplossen. ‘Wie pakt het op, wie lost het op.’ Soms moet je je daar even door aangesproken voelen.

Wat trouwens ook betekent, Frank, dat het een ander issue is dan je in je post linkt!

Watching a livestream by @jlengstorf and @waterproofheart trying to make Bridgy work on a Netlify app. Lot of debugging still, with unhelpful errors.

Edit: they just brought next-netlify-webmention.com to solve the problem.

On Private Commenting Systems

Jan-Lukas wrote about an article by Matt from Write.as called Towards a Commenting System. The article describes a commenting system with two flavour: private and public. For private comments, an e-mail to the author is used; for public comments, one is prompted to publish the comment on their own space first and then notify the original post. It feels very IndieWeb friendly.

Then, Jan-Lukas points out his own site already does this with webmention (as does mine), and that he also has a contact form, which people could use to reply private (at the time of writing I have no contact form).

I like the idea of private comments taking another route than public comments. Just having a contact page is not the same though: to complete the idea you can link it with a call-to-action underneath your posts. Let’s not have illusions here: most people will probably not read my posts on my site but in their reader or some other syndicated copy. But, it would give a nice UX for those on my site.

It also reminds me of how stories on Instagram work. There is a text box underneath it, which the user can tab to type a message. This message is then sent as a direct message to the creator of the story, and not visible to anyone but the creator and the commenter. It seems to work in that context: I do reply to friends in that way sometimes, because it feels very personal.

Another point is that this keeps private comments easier to implement for some and actually possible for those with static generated sites. My site has a way for visitors to log in, and I can build some form of private comments in that way. It is, however, way more work to build and maintain a site that does this, and not everyone is willing to do so. Doing private comments via a different channel makes it easier to have them.

The flip-side is that private comments cannot be shared among a group in this way. If you open a post to a certain circle of friends on, say, Facebook, all those friends can comment and also comment on each other’s comments. This kind of interaction is very hard to do, though, if you don’t have the luxury of a central service that guards access to all the posts — like Facebook does.

The conversation is also more likely to be ephemeral, for there are only two readers, both responsible for keeping their copies, with no help of, say, the Internet Archive.

I remember a moment at IndieWebCamp Brighton when a session about private posts was about to start. Jeremy Keith walked out of the room while making a comment that he didn’t see private pages as something the Web needed. This does not mean I can’t have them, but it did make me think about why I want them and what they would mean to the Web and the world.

By putting the private comments on a separate channel, you are also removing them from the Web. This makes the Web a place for open and public conversations again. (Again: one could argue that thing on the ‘Private Web’ are not on the Web either.) The last few months I’ve been reading more blogs and I must say I really enjoy that open Web.

The separation of private comments creates a clearer boundary between the open and the private, and maybe that’s a good thing. It makes an easier question: it’s harder to answer “which people should be able to read this post?”, than it is to answer “does this concern only me and the author, or could there possibly be someone out there who’s interested?”.

No real plans for removal yet, but I keep being torn about private posts.

Remote attending IndieWebCamp London #indieweb

Introducing dark mode

Like a few others this IndieWebCamp I added a dark mode to my website.

With iOS 13 having a dark mode, which toggles with sunrise and sunset if you want it to, I all of the sudden like to have it on. And yesterday in the train, I noticed that my site felt kind of bright.

So this morning I hacked it together in the train back to Amsterdam. I went the dirty way: just have one media-query for determining dark mode, and then target a lot of elements and classes inside that, and set their color to be something different.

The actual implementation was not that hard (@media (prefers-color-scheme: dark)), but I spent the most time of the traintrip figuring out which darker grayscales should replace the brighter grayscales.

One thing to note here was the tip by Steve Schoger I remembered reading: dark modes are not about just inverting colors. Important elements in your UI should still be brighter than others.

Luckily, I don’t have a very complex UI on my weblog, but it’s worth to note that I took some time to make my month overview pages look nice in both modes. Feel free to compare the two.

Note that I currently don’t have a switch on my site to make you choose, but if your browser / OS tell my site which mode it’s in, my site will adapt to that.

I just released a completely rewritten version of Gimme A Token, which hopefully does a better job of explaining the IndieAuth flow as you go.

I might have to POSSE manual for a while, for Twitter already blocked me once when following a few people at once, but: got a new Twitter account to talk and read about codes and web! #indieweb #manualuntilithurts

Nice! Ik deed dit inderdaad ook een tijdje: checkins kwamen niet voor in mijn feed, evenals antwoorden zoals deze. Antwoorden staan er nog steeds niet in, maar sinds ik mijn checkins achter een login heb geplaatst, staan de paar die ik wel publiek weergeef gewoon in de hoofdfeed.

Daarnaast heb ik verschillende pagina's voor likes, bookmarks, replies, etc., en je kan ze allemaal afzonderlijk volgen. Ik heb zelfs een aparte feed voor Engelse posts. En dat bracht me op het idee: misschien moet ik een pagina maken op mijn weblog, waar iemand zelf een feed kan samenstellen. Gewoon, een formuliertje waar je kan zeggen: dit wel, dat niet. En dat formulier berekent dan een URL waarop precies die content met die filters staat.

Want het is natuurlijk leuk als RSS-feeds kunnen filteren tussen wat ik publiceer, maar het is efficiënter voor ons beiden als ik je geen posts stuur die je sowieso niet wil zien.

Private posts: the move of the checkins

Can I tell you a secret about writing software? We all just wing it. We all try to write the code as beautiful, readable and maintainable as we can, but in the end of the day, the business wants our projects to be done yesterday, not in three weeks. So despite best intentions, corners are cut and things that should not know about other things are calling each other. Some call this spaghetti.

I will also not lie to you: the codebase of this here weblog, at least in it’s current form, is not free of spaghetti or mess. Corners were cut in a time where I did not know there even were corners to begin with. I improved the code many times, all in different directions, because you’re always learning better ways to do it (and I still do). Some call this a legacy codebase.

Because of the shape the code is in, I did not want to add large features anymore. I wanted to rewrite it, of all of it. But as Martin Fowler said somewhere: the only thing you will get from a Big Bang Rewrite, is a big bang. It’s better to incrementally improve your application, so I tried. I tried to come up with clever strategies to do so, to keep parts of my site running on old code while the rest was fresh and new. In all those strategies, my blog entries would be last, because they are with 9000+ and need to be moved all at once.

In order to support private posts, however, it is precisely the code that serves my blog entries that needs work. This means that, while I have private posts very high on my wishlist, I postponed it to after The Rewrite. And I kept attempting to get there, but since it’s a big project for sparetime hours, private posts where impossible for a long time.

The year of the private posts?

Recently, the call for private posts became louder again. Aaron Parecki is trying to get a group of people together to exchange private posts between Readers. I would like to be one of them. In some regard I’m already ‘ahead’ of the game, because I do support private posts on my site already since 2017. The thing is: you need to know the URL of the post to actually read it.

I’ve attended both IndieWebCamp Düsseldorf and Utrecht last month. At the first one, we had a very good session about the UI side of private posts. The blogpost I wrote about it unfortunately stayed in draft. The summary: I used to denote private posts by adding the word ‘privé’ in bold below the post, next to the timestamp. Since the hackday I now show a sort-of header with a lock icon, and a text telling you that only you can see the post, or you and others, if that’s the case.

A big takeaway from Düsseldorf was that I don’t need to do it all at once. To me, the first step to private posts is letting people login to your site. This can be done with IndieAuth, or by using IndieAuth.com (which will move to IndieLogin.com at some point). The second step is to mark a post as private in your storage, and only serve it to people who are logged in. The third step is to add a list of people who can see the post, and only show it to those people. This is the place where I was at.

The fourth step should then be: show those private-for-all posts in your feed, for anyone logged in. The fifth step is to also show those private-for-you posts in their feed, which is tricker but not impossible. The sixth step would then finally be letting the user’s Reader log into your site on their behalf. I feel like I have seen that sixth step as the next step for way to long. By making it the sixth step, it is now only about authentication / authorization, not about what to show to who (because you got that already).

A bonus step could then be to add groups, so you can more easily share posts with certain groups of people. I have wrote about the queries involved before. This is a bonus step, because it’s making your life easier as maintainer of the site, but it is invisible to the outside world. (I would prefer not to share to people which groups they are in, nor the names of the groups the post was shared with. Those groups are purely for my own convenience.)

Of course, you can take different steps, in a different order. But to me, this is the path to where I want private posts to be.

Channeling my inner Business Stakeholder

After breaking it down into these nice steps, I’m still left with a legacy codebase. My biggest takeaway from Utrecht, was that I should be more pragmatic about it. The code quality of my site is only visible to me, what matters is the functionality. And I want this private post functionality.

I still did some refactoring that could be useful to future versions of this site, but I won’t bore you with that. I decided that it was not worth the wait, and that private post feeds should be part of this version of my blog.

Last Tuesday, there was yet another chat about private posts and how to do it. There was a question about the progress, whether or not something was decided at the recent EU-IWCs. But there is no decision, there is no permission, there is no plan to be carried out. There is just us, wanting to use this feature that does not exist yet. The only way to actually get there, is to build it ourselves and see what works and what doesn’t.

So I hacked it together, in my existing code. I believe I broke things, but I have fixed some. If you see more, please tell me. But I got the functionality, and that is what counts.

Marking all my checkins private

There is this app called Swarm. Some members of the IndieWeb Community use it, because it’s fun. I would call it the Guilty Pleasure of the IndieWeb, the last Silo. I use it too, especially when I’m in a city for IndieWebCamp. It’s almost impossible not to use it then: the people I’m with are checking me in anyway.

I like having a log of every bar, restaurant, shop I have been, and I see value in sharing it. But it also creeps my out to have all that information about me on a public place like this. Even on Swarm, checkins are only shared with friends (and advertisers), not the public. It seems to me that my checkins, then, are the perfect place to start with private posts.

So that is what I made: I marked all my checkins as private-for-all. This means they are still public at the moment, but you need to log in, which currently rules out bots and practically every visior. But chances are you know how to use IndieAuth, or have a Twitter account. You can then login to my site by clicking the link in the upper right corner. After you logged in, you will see all my checkins appear in the main feed, each of them with a message that it’s only visible to logged in users.

In addition, there is a new page: /private. The link will appear in the menu when you are logged in. This page shows you all the private posts that are specificly shared with you. Some of you might actually see a post there.

Steps

One part of me says “but is private-for-all private enough for my checkins?” Another part of me says “it’s nice that you support the feature, but no-one is going to log into your site.” Yet another part of me says “what is it worth, writing more code in this codebase you want to get rid of anyway?” But it’s fine. I made a step, that’s what’s important. From here, I can look into AutoAuth, and maybe, maybe, we can get some private feed fetching to work before IndieWebSummit.

But in the worst case: I own my checkins, and I control who sees them. And that’s a very nice place to be in.

check-in bij 's-Hertogenbosch Railway Station (Station 's-Hertogenbosch), 's-Hertogenbosch

check-in bij 's-Hertogenbosch Railway Station (Station 's-Hertogenbosch), 's-Hertogenbosch

Traveling with The Bag #indieweb

Switched my design from using a grey background with white backgrounds for the posts, to a white background for both, and a light fading box-shadow around the posts. I am very pleased with the results!

My site broke, because the /2019 folder in my storage did not yet exist, and somewhere over the last year I added code that relied on that. So 19 years in, the Millennium bug is still active.

Just implemented a Siri Shortcut for IndieAuth! Now let’s see if I can integrate it with my Micropub shortcut.

Twitter

Twitter Instagram

Instagram LinkedIn

LinkedIn Github

Github Strava

Strava Facebook

Facebook